PIMS® pioneered Customer Value measurement and generated the evidence on how central it is to business strategy. PIMS® developed Customer Value Management as a discipline for strategy development, pricing decisions, market segmentation, and process improvement. Customer value comes as close to being a panacea for business problems as anything else that has been suggested to date.

Businesses offering customers preferred products or services at better-than-fair prices are more profitable and gain market position more rapidly than those offering inferior value (though there is a moderate cost for getting to superior value). This is an extremely fortunate alignment of virtue and reward. The only real reason for your business’s continued existence is that you provide customer value (if clearly better options exist, what are you really there for?) – but the fact is that this is also in your own self-interest too.

The basic facts

The basic facts

The basic facts let us first define customer value: it is the combination of customer preference and relative price.

- Customer preference looks at this business versus competitors, from the specifying customer’s point of view, on all the non-price attributes that affect the purchase decision. The “wins” (better than competitors) and “losses” (worse than competitors) are totted up across all competitors and all attributes (weighting by importance), resulting in a customer preference score that is the net % wins minus % losses. Note that this metric is not just “customer satisfaction”: it includes non-customers, is relative to competitors, and reflects not just the product itself, but also the service and image factors affecting choice. Though we sometimes use the word “quality” to describe this dimension, it is much more than “quality” in terms of how well you meet specifications.

- Relative price is designated as “low” when the business’s selling price is less than that charged by competitors, 100% when it is the same and “high” when there is a meaningful price premium.

Customer value is NOT the lifetime net present value of a customer’s cash payments to you (weighted by retention probability): a metric often used in utilities businesses. We are looking at what the customer gets from you, not what you get from the customer.

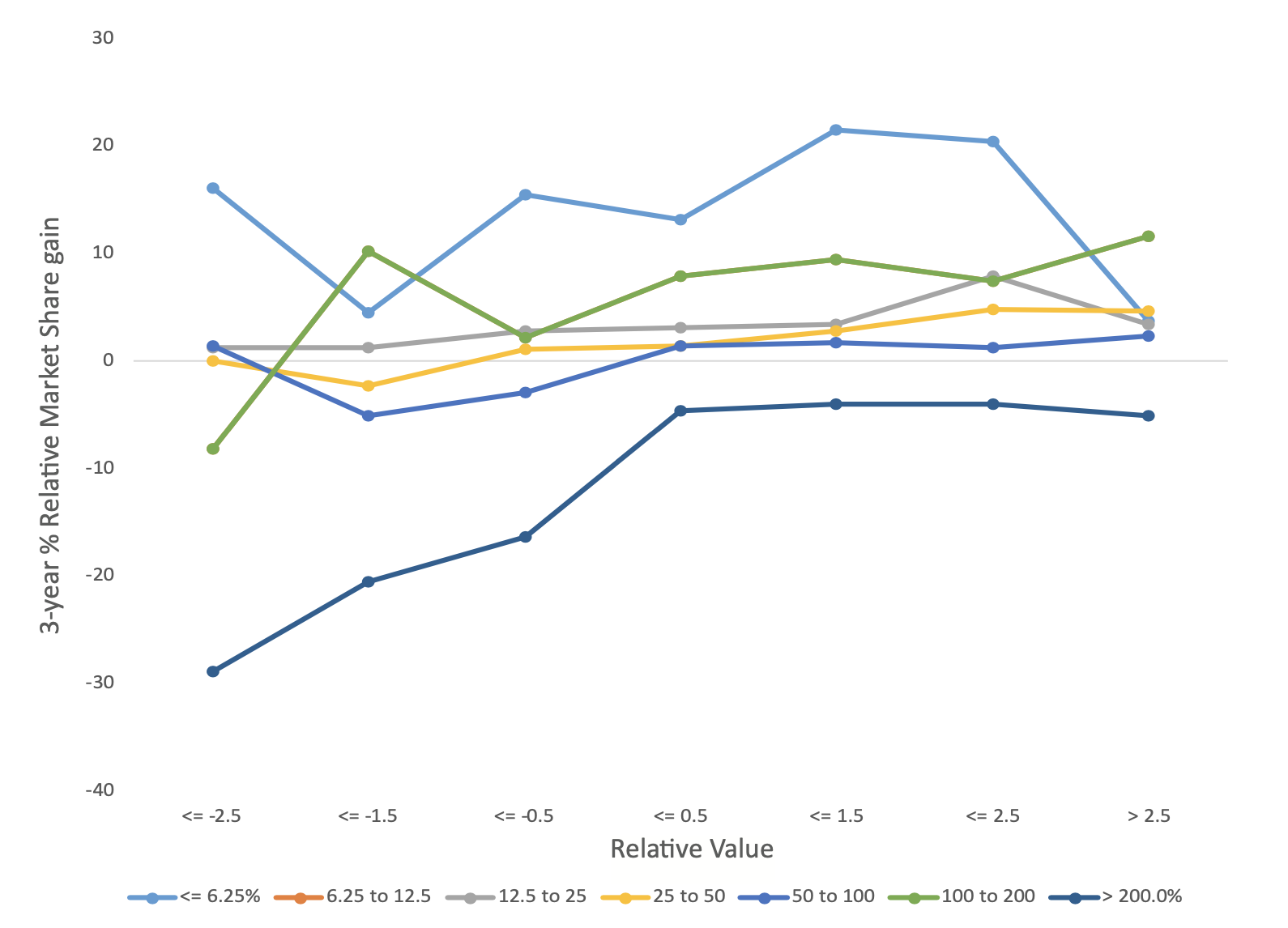

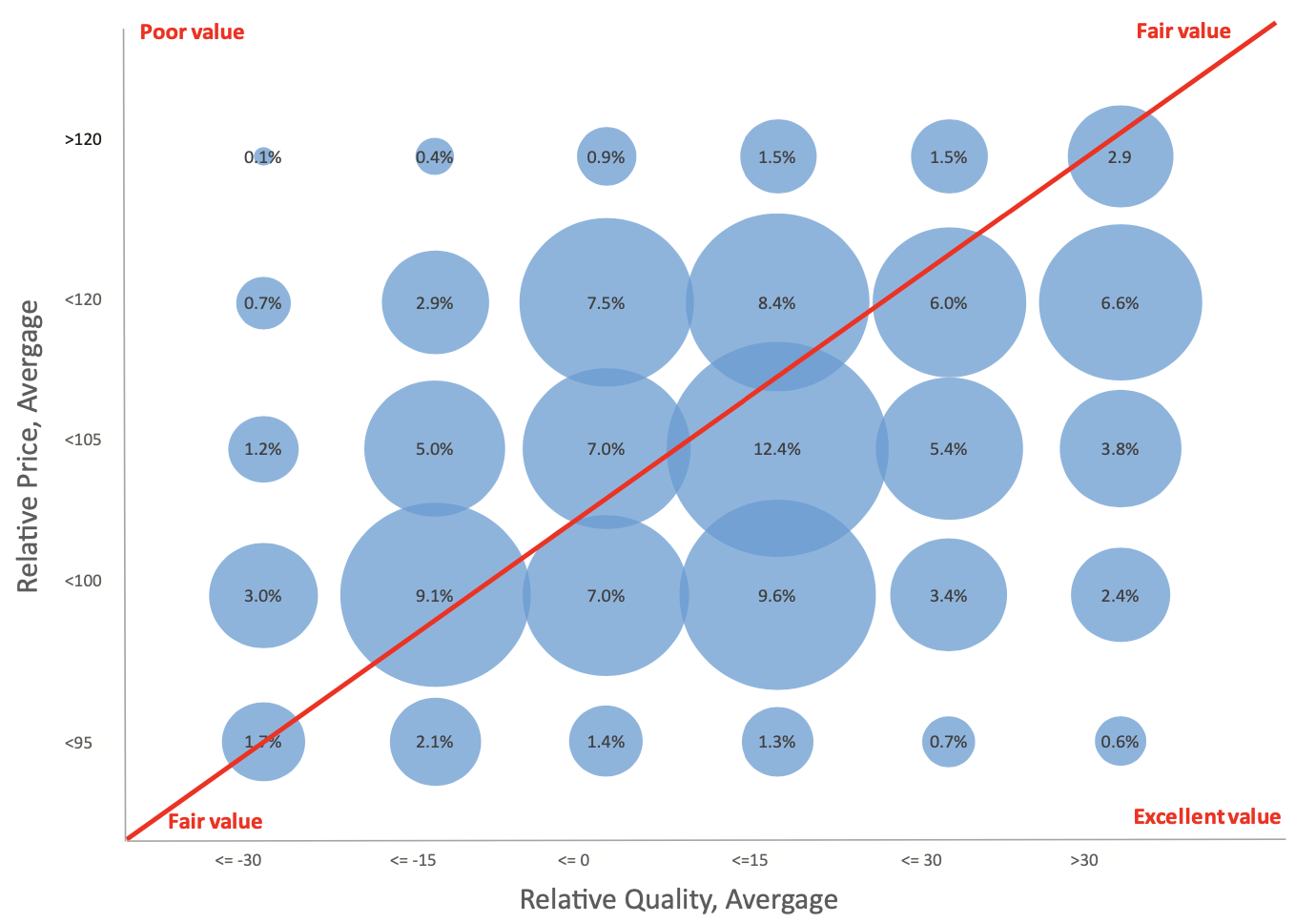

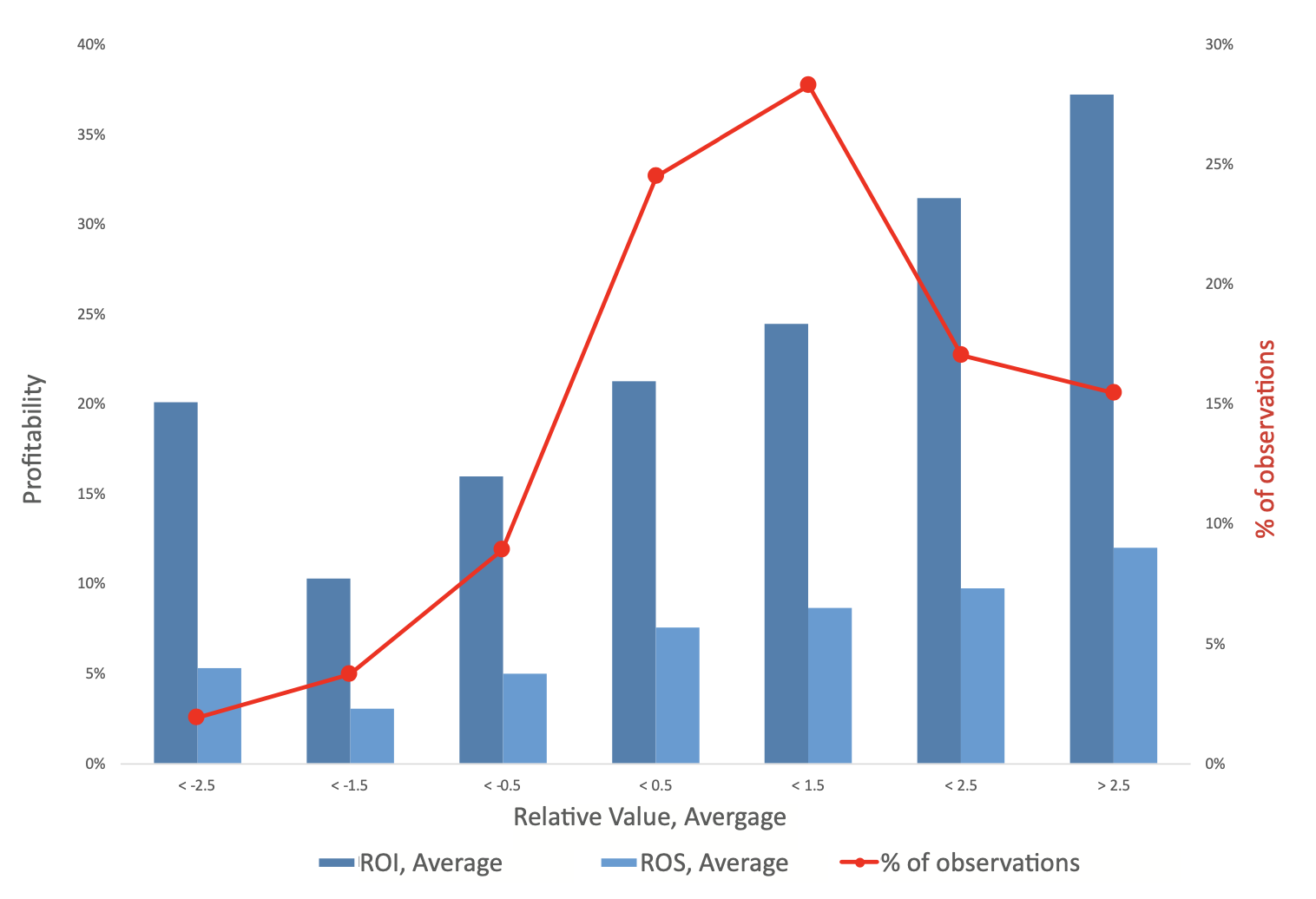

The following illustration (Exhibit 1) is a value map. The customer preference and relative price axes represent the statistical distribution of businesses in the PIMS database in terms of these two variables. Most businesses fall along the diagonal line, i.e. businesses reporting strong customer preference also tend to report higher prices, while those that discount relative to competition also tend to have inferior quality. But there are also quite a few businesses which, through accident or design, wind up in an ‘unusual’ position – either no premium for strong customer preference or charging apremium for negative customer preference.

Figure 1: Distribution of PIMS businesses on the value map (PIMS® 2023 research)

Note:

ROI = return on investment: earnings before interest and tax as a % of the fixed assets (net book value) and working capital required for business operation.

ROS = return on sales. Relative value is on a standardized scale of distance from the fair value line.

Here, as in all other exhibits in this document, we are looking at ~4,500 businesses in the PIMS database, suitably arranged.

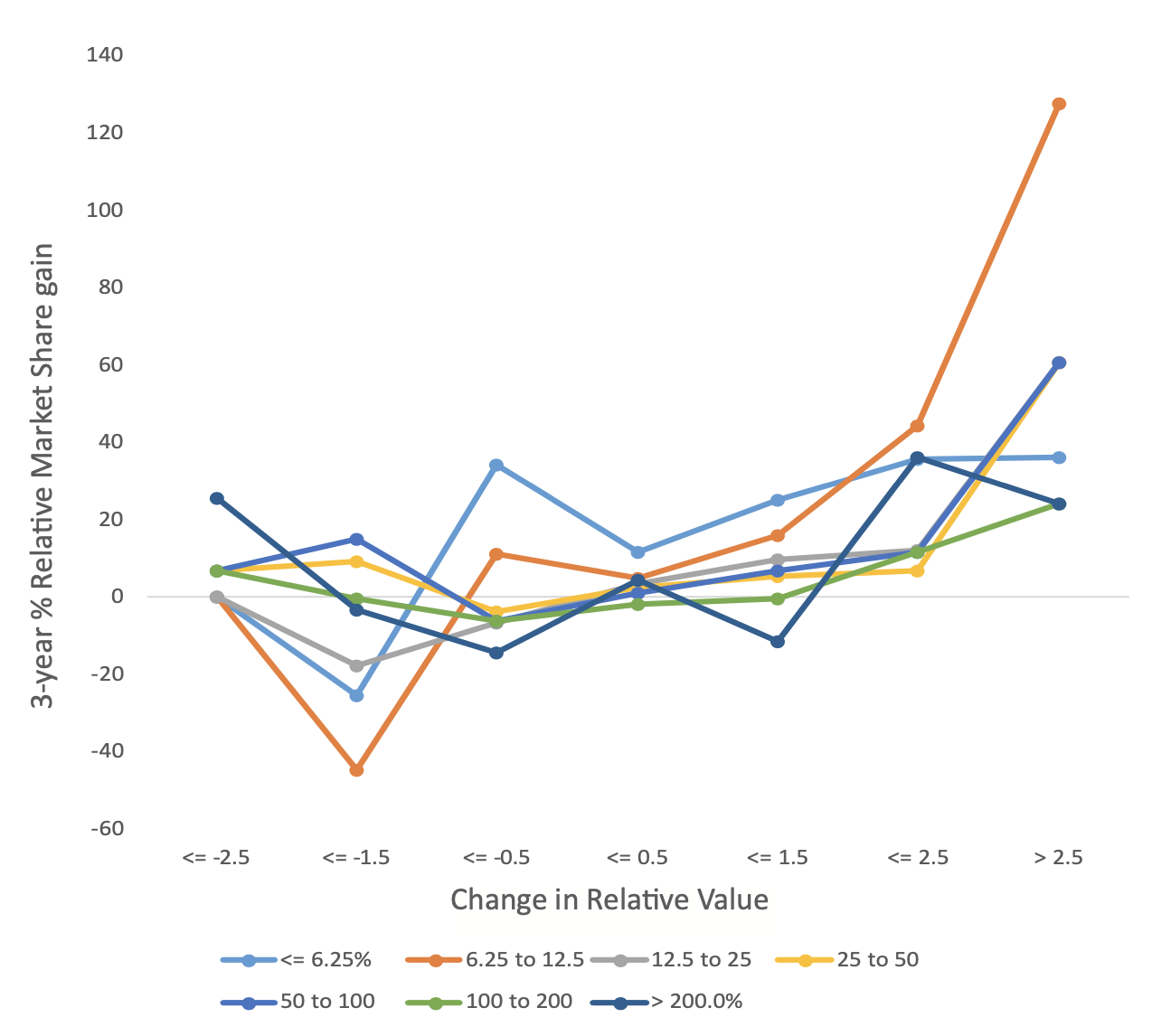

From Exhibit 2 it is clear that superior value leads to better profitability. To look at the effect on market share gain (Exhibit 3), we need to correct for the initial level of market share, because share moves tend to be dominated by “the mathematics of dissatisfaction”: market leaders, despite having a lower percentage of dissatisfied customers than others, tend to have a higher absolute number, who then switch to competitors at random. Consequently, high share players tend to have both superior value and high share loss.

NB we use relative share (this business as a percentage of the three main competitors combined) as it is less sensitive to served market definition.

The apparent facts are (1) that the market values quality so highly that it is willing to pay more for it than the incremental cost of producing quality, and (2) that the market is so happy about not having to pay a premium price for “value” that it is willing to reward the seller to the extent of granting him a disproportionately increased share of the market. Finally, the evidence shows that poor value is associated with high and ineffective marketing efforts, which have a direct hit on the bottom line.

So far, we have focused on the effects of excellent versus poor value. What about value change? The findings are in Exhibit 4; apart from a few extreme under-populated cells, improving value also helps share gain.

Figure 2: Customer value helps profitability (PIMS® 2023 research)

In principle there are two ways to improve value: increase The “difficult” option of improving non-price attributes quality or cut price. PIMS evidence suggests that the is the one that competitors actually find it hard to copy. latter is only feasible over a reasonable timescale if you

have a strong cost advantage on key inputs of labour, materials or capital. Otherwise, competitors just follow.

Some caveats

Some caveats

Before rushing out to offer the market greater value, as every business person should clearly be tempted to do, it is necessary to observe a few cautions.

While value is clearly profitable, the growth in market share does frequently act as a drain on cash. It requires cash in the forms of both greater capacity and also greater working capital. Therefore, a capital intensive business in a cash bind may need to forego the market share benefit and take only half the loaf, in the form of a premium price.

What if everyone in the industry attempts the same approach? Not everyone can win this game, since both customer preference and price are relative concepts here. The idea is not to offer a good product and to charge a Iow price, but to offer a better product and to charge a Iower price as compared to the other fellow. So, it makes sense to assume that superior value can be exploited successfully only by businesses that already have a running start in that direction, a genuine cost or technology advantage, and an appropriate public reputation.

For many products, particularly consumer products, there are two value maps: for the end-consumer and for the immediate customer. For the former, superior value means better product/availability/price, for the latter superior value means a higher margin, better service/delivery/image, and high end-consumer pull. Overall customer value is a combination of the two, and there is a clear need to walk a tightrope between low end-consumer price and high trade margins.

Life is complicated, and certainly business life. Achieving superior value requires changes in raw materials, supply chain organization, product and process innovation, sales and marketing efforts, service, pricing and attitudes. Therefore, be suspicious of all simple maxims. There is no way of being very confident that any strategy is right for a particular business without working out that strategy in detail, with all the major required actions specified, and testing that strategy against relevant evidence.

Value for the weak

Value for the weak

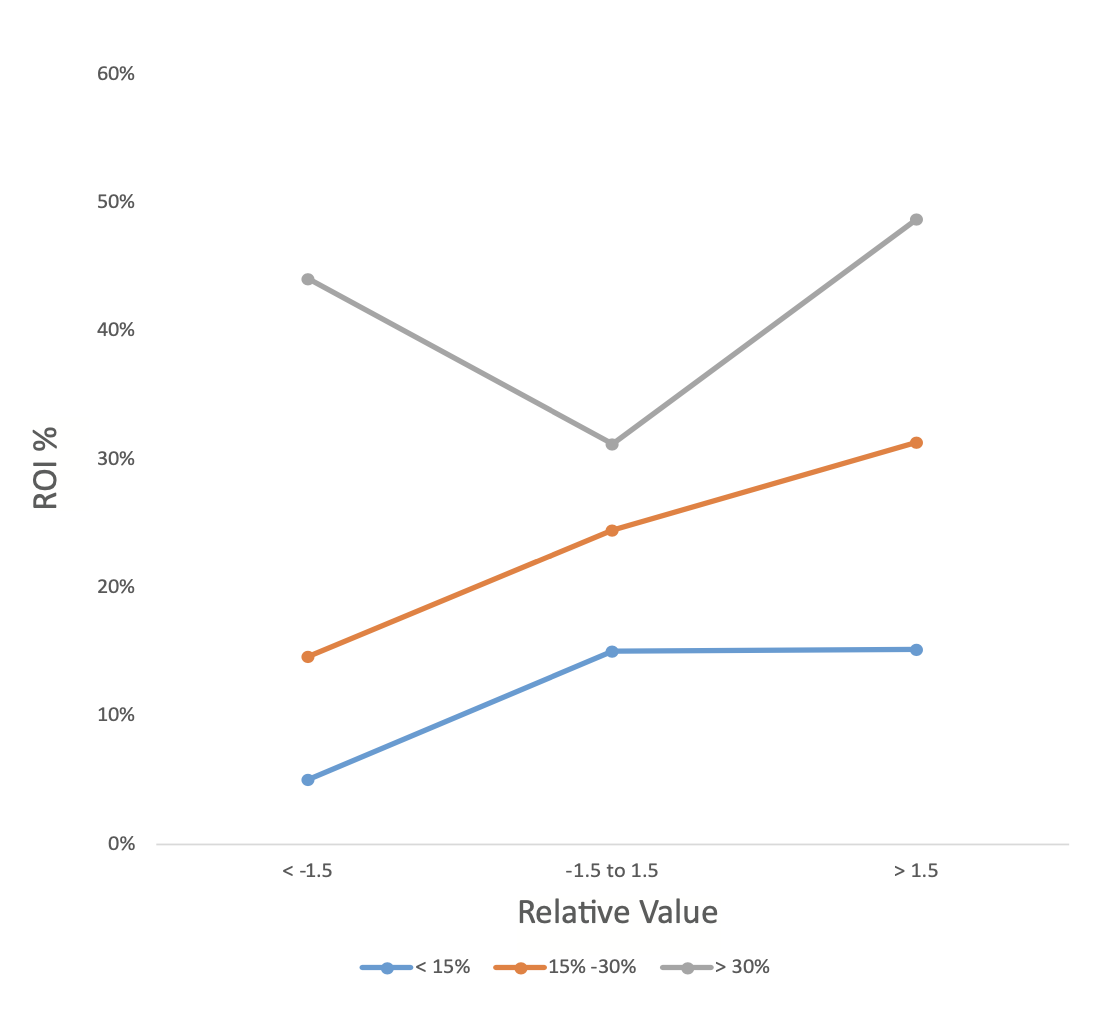

Superior value is particularly helpful to businesses with low market shares; in fact, offering value can offset some of the disadvantages of low share in making the business profitable (Exhibit 5). The effect is not as important in terms of ROI for high-share businesses: a small number make very good profits (but lose market share rapidly) by “skimming”, i.e. charging a higher price than justified. They can also make similar ROI by offering high value to their customers; the low point is undifferentiated value. Superior value can be an important part of a strategy to get and to keep market share. Low-share businesses offering high value gain share twice as fast as those offering low value. Moreover, businesses that have already successfully obtained high market share are disproportionately likely to be offering high value.

The robustness of value

The robustness of value

The impact of customer value on operating performance is not just pervasive; it is stable over a number of different definitions of “value”. The exhibits shown are based on a formulation of value in which customer preference and relative price are weighted by asking customers about their price/quality sensitivity. In order to find out what would happen in markets where customers misjudge their price sensitivity, we tried a wide range of equal price sensitivity weights, and repeated the analysis. The result: none of the strategic messages shown here changed even in strength, let alone in direction. The same results also came out using “imputed” weights based on the observed range of prices and customer value scores.

Another analytic experiment was to ignore the impact of price for high quality products, and to increase the price weighting progressively as quality fell. This was to test the assumption that the purchaser of a high quality product is essentially unconcerned about its price, while the buyer of a low quality product is very concerned about price. In other words, value for the first buyer may be found entirely in the high quality of the product, and value for the second may be found in low price. Again, the strategic messages shown here retained their full strength.

Finally, knowing that relative value is positively correlated with market share, and that businesses with high market share tend to be more profitable than low share business, we adjusted ROI for the effects of market share (and of investment intensity as well) and then observed the residual profit impact of customer value. Once again, the strategic benefits of superior value remained strong and clear.

Figure 5: Value helps profitability most for low and medium share businesses (PIMS® 2023 research)

Some conclusions

Some conclusions

Customer value and operating success are closely related, and in most situations, the relationship is strong. The attainment of a superior value offering, while attractive, may not be cheap or easy. Value is a strategic characteristic relative to competitors; they may choose not to allow your price to fall, or your quality to rise, relative to their own. Steps to increase value may carry costs, either for research or other means to improve product compared to the cost and difficulty of the road to attaining it. If the balance is favourable, as it seems to be in most cases concerning customer value, then the move is indicated.

It is a piece of good news for the economy at large that it is profitable for so many business firms to aggressively fight inflation by resisting price increases. The benefits are enjoyed by quality, or in the form of reduced margins in the short term as prices are lowered. So, as always, the desirability of having attained an attractive strategic position needs to be all.

Please click here to download the article as a PDF.